Over the past decade, I’ve led numerous IT transformations — some involving moving systems into the cloud and others focused on bringing them back. During this time, I observed two strong and seemingly opposite trends emerging in parallel: Cloud migration and cloud exit. At first, these directions may seem contradictory, but both are gaining momentum — and both carry significant financial implications that are often misunderstood or oversimplified.

This article is my attempt to bring clarity to the topic. I want to explore what really happens when companies choose the cloud or choose to leave it. Not in theory, but in numbers. I will examine the financial impact of these decisions using real-world examples and patterns I’ve encountered across organizations of various sizes: Startups, mid-sized companies and large enterprises. Depending on where your company is in its growth journey, the cost balance can shift dramatically.

My goal is not to promote one model over another. Instead, I want to help decision-makers evaluate both cloud-first and cloud exit strategies from a financial standpoint. While the technical considerations are important, this article focuses only on the financials: ROI, long-term cost models and how to assess whether your current path still makes economic sense.

The Lack of Clarity Around Cloud Exit ROI

Why now? Because for many businesses, cloud bills are becoming increasingly difficult to predict and even harder to justify. The pricing model of cloud services may seem flexible at first: Pay for what you use, scale as you grow. However, over time, if not tightly managed, these costs often grow faster than expected — especially when no one is clearly accountable for budget tracking. Resources may expand quickly and unpredictably just to meet delivery deadlines.

Repatriation or cloud exit does not mean ‘going back in time’. It means rethinking. It is an opportunity to ask: Which workloads are still a good fit for the cloud? Which would be more efficient, on-premise or in a hybrid model?

In the following sections, I will walk through financial models, key cost indicators and clear calculations that reveal the true ROI of both staying in the cloud and exiting it.

Cloud Migration and Cloud Exit Statistics

Today, nearly every company is in the cloud — at least partially. Approximately 96% of businesses globally now use some form of public cloud services and 84% have adopted private cloud environments. These figures highlight how deeply cloud technologies have become part of modern IT operations. At the same time, however, another trend is emerging — one that can no longer be ignored — cloud exit.

Let’s start with cloud adoption. Among startups and smaller businesses (fewer than 1,000 employees), cloud usage is very high: Approximately 63% of their workloads and 62% of their data are now placed in public cloud environments. For mid-sized companies (1,000 to 2,500 employees), around 41% are still in the process of planning or evaluating their cloud strategies. Among large enterprises, more than half are doing the same. In short, cloud migration remains active across all business segments. However, the rate of new adoption is slowing and the focus is increasingly shifting toward cost optimization.

Now, here’s where things get interesting. In parallel with rising cloud adoption, a significant portion of companies are also moving workloads back out of the cloud. According to recent U.S. data, 42% of companies have already repatriated at least part of their workloads or plan to do so in the near future. This is not a one-time anomaly. In previous IDC surveys, up to 80% of companies reported some form of workload repatriation within a year. The trend is real and it is growing.

What is driving this reversal? The top two reasons are cost and security. Approximately 43% of IT leaders said their cloud costs ended up higher than expected — often realizing this only after implementation, when monthly bills began to exceed budgets. Another 33% cited security and compliance concerns, areas where some organizations feel greater control when managing infrastructure directly.

Across company sizes, the signals are similar. Smaller businesses often exit the cloud when pricing models turn out more expensive than expected. For mid-sized and large enterprises, cloud exit typically results from strategic reassessment. In both cases, repatriation is not about abandoning the cloud entirely — it is about choosing where the cloud continues to make financial and technical sense.

From my own experience, I can confirm this shift. The story I have seen again and again is not ‘cloud versus no cloud’, but rather ‘cloud where it works and alternative solutions where it does not’. For any company managing at scale — especially those dealing with legacy systems or strict compliance requirements — hybrid and multi-cloud models are becoming the practical middle ground. However, the key factor behind these decisions is almost always financial.

Understanding these statistics brings realism into the conversation. Cloud migration is not a one-way street — cloud exit is part of the broader strategy. For many companies, it may be the only way to regain control over budgets and align infrastructure with long-term business goals.

Typical Examples of Companies for the Calculation of Cloud Exit ROI

To understand the real ROI of a cloud exit, we need to move beyond general opinions and focus on real numbers. To do that effectively, we must define typical company profiles — because a startup does not think like a bank, and a 300-employee company faces different risks than a 2,000-employee enterprise.

For this analysis, I use three common company sizes:

- A startup (approximately 25 employees)

- A mid-size company (around 300 employees)

- A large enterprise (2,000+ employees)

These categories allow us to build practical financial models that reflect real-world IT environments — from solo generalists to large teams.

Let’s start with the startup. In a cloud-first setup, infrastructure tasks are typically outsourced or handled by a DevOps engineer or full-stack developer. On average, this translates to less than one full-time person managing infrastructure. Most startups use a combination of software as a service (SaaS) tools and basic infrastructure as a service (IaaS) for development or analytics. Their annual cloud staffing cost is roughly $60,000 and infrastructure costs add another ~$19,500 (with cloud’s typical +30% pricing premium). Compliance and security (ISO, SOC2, PCI DSS, GDPR, etc.) adds ~$80,5000/year, if needed. This brings the total annual total cost of ownership (TCO) to around $160,000.

In contrast, if the same startup goes with on-premise infrastructure, it usually needs 1–2 IT generalists to manage backups, networking and devices. That is ~$90,000/year in staff cost and $10,000 in infrastructure. Add in security and compliance (often more complex and manual in on-premise setups) and total costs rise to $210,000–225,000/year. Bottom line: For most startups, the cloud is not just simpler — it is cheaper.

Now look at a mid-sized company with 300 employees. They typically have a mixed environment — some SaaS, some on-premise servers and a growing cloud footprint. An on-premise model would require around 15 IT staff (~$900,000/year), ~$120,000 in infrastructure and another $577,000 for compliance, audits and tooling. That adds up to over $1.5 million/year.

In the cloud, the same company might reduce IT headcount by ~30%, shift more responsibility to the cloud service provider (CSP) and hire 8–10 cloud-savvy staff for identity and access management (IAM), DevOps and FinOps. That is about $600,000/year. With infrastructure costs rising to ~$234,000 (factoring in the cloud premium) and compliance falling to ~$397,000 (due to managed services and automation), the total cost drops to ~$1.23 million. That’s around $270,000/year in savings, if managed well.

However, things change at enterprise scale. A company with 2,000+ employees may already have 30–40 on-premise engineers and system administrators, costing ~$2.4 million/year. These teams often manage their own data centers, sometimes with thousands of servers. Their annual infrastructure and compliance cost typically ranges from $4.8 million to $6.0 million.

In theory, the cloud removes the need for physical infrastructure. Although in reality, those savings are often offset by new roles — FinOps teams, platform engineers, cloud architects, compliance auditors and security specialists. Staffing costs rise to ~$3 million/year, infrastructure to ~$2.6 million (before egress and optimization) and compliance reaches ~$1.08 million. Altogether, the cloud model for a large enterprise can total $6.6 million or more annually, often exceeding the cost of a well-managed on-premise setup.

What this shows is the hidden complexity of scaling cloud operations. Cloud does save time on hardware, but it adds new financial layers. Governance, security, billing management and cost control — these roles did not exist in traditional IT environments, and now they are critical. If you lose visibility or control, the cloud bill becomes just another data center, but without the budget borders.

When evaluating cloud exit, do not just compare server costs. Compare staffing models. Compare compliance workloads. Compare the complexity of cost visibility. Use your own numbers, your own organization chart and your own needs, and ask: Where is your turning point? For some, the cloud will still make perfect sense. For others, it may be time to step back, recalculate and exit the cloud where it no longer adds value.

Cost Modeling: How to Calculate the Turning Point

Once we have seen the total yearly cost of cloud versus on-premise across different company sizes, the next natural question is: Where exactly is the turning point? That moment when the cloud stops being the most cost-effective option and a partial or full cloud exit starts to make sense.

To answer this, we need a comprehensive model — not just infrastructure costs, but the real-world expenses that arise during a transition. Because cloud exit is not free and it is not instant. It takes time, people and parallel infrastructure support.

Let’s walk through what this looks like in practice, using the same three company types — startup (25 employees), mid-sized company (300 employees) and enterprise (2,000 employees).

Each of these companies has different cloud usage patterns and internal capabilities. However, they all follow the same core logic when modeling TCO:

- IT Staff Costs – Number of engineers, operations personnel, cloud roles, platform support

- Infrastructure Costs – Cloud services or on-premise servers and licenses (Reminder: Cloud infrastructure is, on average, 30% more expensive due to vendor margin and scaling overhead.)

- Compliance and Security Costs – Certifications, audits, governance

- Overhead – Management effort, HR, procurement, budgeting

To calculate the true turning point, add two more factors:

- Cloud Exit Team – A project team dedicated to analysis, strategy and execution

- Parallel Operations – Infrastructure does not migrate all at once. During transition, companies must run both cloud and on-premise environments.

Let’s look at real numbers over a five-year horizon:

Startup (25 employees)

- On-Premise TCO (5y): $1.025 million

- Cloud TCO (5y): $800,000

- Cloud Exit Team: +$260,000

- Final Cloud TCO (with project): $1.06 million

- Difference: On-premise is still ~$35,000 cheaper, but not significantly.

Conclusion: Cloud remains cost-efficient and flexible. Cloud exit is unlikely unless driven by other strategic goals.

Mid-Sized Company (300 employees)

- On-Premise TCO (5y): $7.985 million

- Cloud TCO (5y): $6.155 million

- Cloud Exit Team: +$370,000

- Final Cloud TCO: $6.525 million

- Difference: Cloud still saves ~$1.46 million over five years

Conclusion: Cloud is financially effective if governance is strong and workloads are elastic. However, watch out for cloud creep and staff duplication.

Enterprise (2,000+ employees)

- On-Premise TCO (5y): $30.5 million

- Cloud TCO (5y): $33.4 million

- Minus 20% Infrastructure Retirement: −$2.6 million

- Plus Cloud Exit Team: +$975,000

- Final Adjusted Cloud TCO: $31.775 million

- Difference: On-premise becomes ~$1.275 million cheaper.

Conclusion: The turning point has arrived. Cloud TCO now exceeds on-premise. A cloud exit, at least partial, is worth serious evaluation.

What exactly do we factor into this turning point calculation?

- Cloud Migration or Exit Team: Typical two-year cost ranges from $200,000 (startup) to $975,000 (large enterprise). This covers strategy, architecture, compliance and execution across all phases.

- Parallel Workload Support: During repatriation, engineers must maintain both environments. This creates temporary staff duplication and increases support workload.

- CapEx Resurgence: Moving out of the cloud requires buying or upgrading hardware, provisioning data center racks and restoring backup infrastructure.

- Retirement Potential: On average, 20% of workloads do not need to be migrated. These may be legacy, duplicated or obsolete. This is a powerful cost-saving opportunity, but only if properly identified during the planning phase.

- Compliance Shift: While cloud offers a shared-responsibility model, on-premise demands direct investment in ISO, SOC and GDPR tooling again. These costs rise — but so does control.

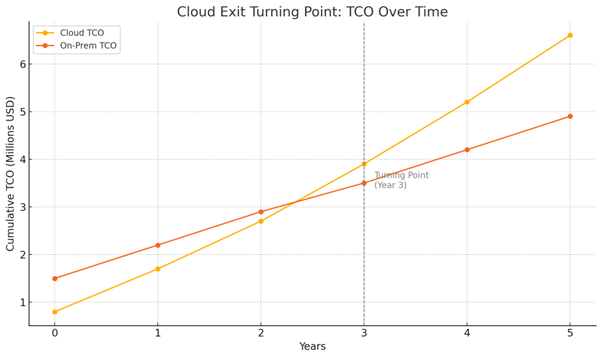

If you plot these costs over time, you will see two lines:

- Cloud TCO continues to rise, driven by premium pricing and increased staffing requirements.

- On-premise TCO starts with a higher upfront cost, but grows more slowly over time.

Where those lines cross — that is the Repatriation Point. It is not tied to a fixed year. It depends on your workloads, staffing model and ability to govern cost.

For many large enterprises, that point has already passed. This is not about one model being ‘better’ than the other. It’s about understanding context, enterprise size, growth stage and operational goals — and then applying the right financial lens.

The goal of this cost model is to give decision-makers a clear, grounded framework — not just for ‘staying in the cloud’ or ‘leaving the cloud’, but for building a strategy that supports scale, reduces waste and aligns with long-term priorities.

Conclusion

Cloud migration was never just technology. It was about speed, flexibility and getting ahead. Now that most companies are already in the cloud, the question has changed. It is no longer ‘Should we move?’ It is ‘Should we stay?’

What I have shared here is not a one-size-fits-all answer. Instead, it is a practical way to think about your own turning point — the moment when the cloud becomes more cost than benefit, or when repatriation starts to make sense. It is a financial perspective, built on real numbers and recurring patterns I’ve seen over more than a decade in this field.

Startups still benefit the most from cloud: Lower upfront costs, fewer infrastructure roles and maximum flexibility. Mid-size companies can also win — especially when workloads are elastic and FinOps discipline is in place. However, for large enterprises, the financial math becomes more complex. When you factor in migration costs, parallel operations and the opportunity to retire unused applications, the balance often shifts back toward on-premise or at least toward a hybrid model with tighter cost control.

This does not mean cloud is ‘bad’. It means we have matured. Cloud is a tool. Like every other tool, it needs to be reassessed as the context changes.

If you are a decision-maker, here is my advice:

- Start with visibility – Know your infrastructure costs, team load and workload patterns.

- Do not guess – Build a cost model across a three- to five-year horizon.

- Include transition costs, staffing changes, compliance impact and expected savings from applications retirement.

- Use your own numbers, not vendor estimates.

- Most of all, do not treat cloud exit as failure. It is evolution.

In the end, this is not a cloud versus server debate. It is a strategy question. The companies that answer it with clarity and confidence will lead the next phase — whether that means deeper cloud investment, hybrid optimization or smart repatriation.

The goal isn’t to be trendy. The goal is to be sustainable.

Key Takeaways

- Cloud migration and cloud exit are not opposing strategies — they are both integral parts of the same digital transformation life cycle. Companies must approach each decision as context-dependent, rather than trend-driven.

- Real-world cloud exit cost modeling must account for more than monthly cloud bills. Staffing changes, parallel operations, transition periods and applications retirement all impact the true return on investment (ROI) of cloud, on-premises or hybrid strategies.

- The financial turning point — where repatriating workloads becomes more cost-effective than keeping them in the cloud — can be calculated, but only when companies include hidden costs such as dual infrastructure support during transitions, capital expenditures (capex), cloud backup retention and more.

- Startups benefit most from the flexibility of public cloud, but large enterprises often reach a scale where repatriation offers better long-term cost control and improved operational efficiency.

- Cloud exit is not a rollback to legacy systems — It’s an optimization strategy. When executed with clear planning, it can reduce expenses, simplify architecture and align infrastructure with evolving business priorities.